by Ilse Gebhard, KAWO member

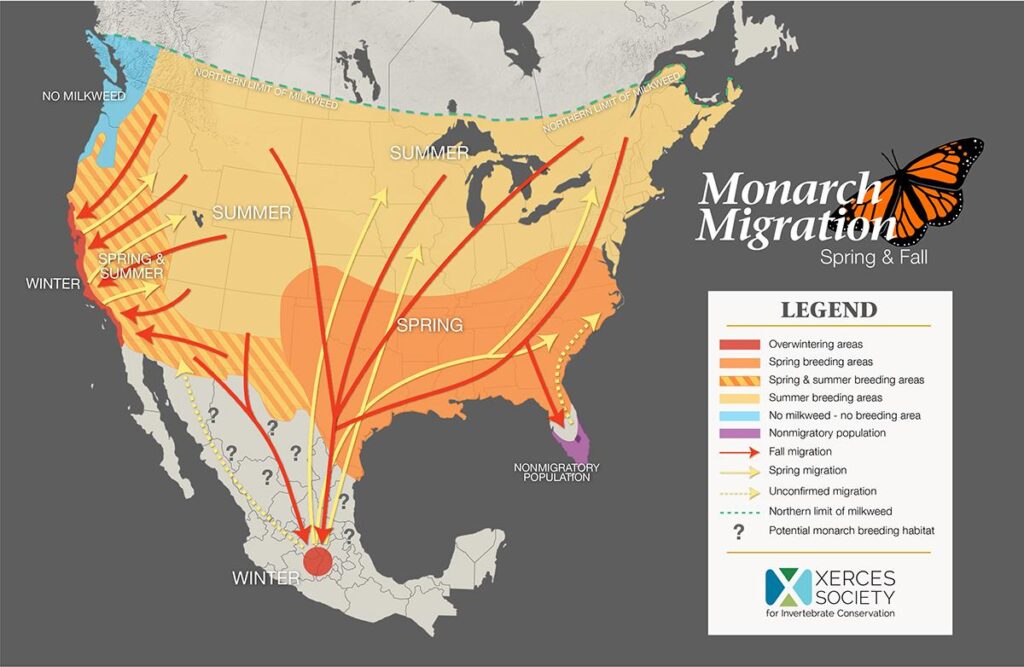

One of the most fascinating natural phenomena is the Monarch butterfly migration in the fall. While it was known that Monarchs breeding west of the Rocky Mountains overwinter on the California coast, it was a mystery where the population breeding east of the Rockies overwintered. It took Canadian Zoologist Fred Urquhart, his wife Norah, and a host of associates nearly 40 years to locate their overwintering grounds in 1975.

Extensive Monarch tagging and recovery studies over those years pointed to central Mexico. It was not as if no one knew where the Monarchs overwintered. Certainly, the indigenous people living in this remote mountainous area knew that each year around Halloween the Monarchs arrived and stayed for the winter. They considered the Monarchs to be the souls of the dead since their arrival often coincides with the second day of November when Mexicans celebrate the Day of the Dead.

The Monarch’s breeding range extends well to the north and east of Michigan. For migrating Monarchs from northeastern Ontario to travel to Mexico by the shortest route they must fly southwest. Many Monarchs pass through Michigan, joining our local migrating population. While this southwest flight pattern can sometimes be observed inland by individual butterflies, in west Michigan the best place to observe migrating monarchs is along the Lake Michigan shoreline. Monarchs avoid crossing large bodies of open water, so when on their southwest journey they reach the lake, they follow it south until they come to the bottom of the lake and resume their southwest flight.

Migrating Monarchs can form overnight clusters, called roosts, in favorable habitat. Identifying such habitat has been one of the goals of Monarch conservation. As with stop-over sites for migrating birds, it is important to preserve habitat for migrating Monarchs. After a birding friend told us that he had seen Monarch roosts at Muskegon State Park, my husband and I visited the park during migration in 2003-2005, and indeed we found Monarch roosts.

Applying what we had learned at Muskegon State Park, I thought that maybe Mt. Baldhead at Saugatuck/Douglas might be a clustering spot. Based on previous experience, winds out of the southeast, south and southwest are favorable for cluster formation. Much to our chagrin, on August 30, the day we had invited some friends to join us in our search, the wind came from the east-northeast. But you go when you can, and who knows what interesting things you might find.

We arrived at the bottom of the steep stairs leading up Mt. Baldhead at 6 p.m. Taking an occasional breather on the way up, we saw a few Monarchs overhead. Finally at the top, through breaks in the trees, we could look down to the beach to the west and the towns of Saugatuck/Douglas to the east. What we saw on both sides was truly astounding – a steady stream of Monarchs floating by on set wings, kept aloft by updrafts and pushed south by the 8-11 mph breeze. Sometimes they went sideways and even backwards and sometimes they twirled around in twos like dancing, presumably buffeted by gusts of wind. Conditions like these allow Monarchs to migrate long distances without expending much energy from the stored fat they need to survive the winter in Mexico.

To put the numbers of migrating Monarchs in perspective, Russ counted 40 of them passing through the limited field of view of his binoculars in one minute.

After watching this spectacle for a while, we decided to break up, one group staying where we were and one group going down to monitor the trees at beach level. This way we could watch two areas for any roosts that might form. Thanks to the wonders of technology, we stayed in contact by cell phone.

Our first report from the beach was that some of those Monarchs were really dragonflies. Wow, two migrations going on! Subsequent one-minute counts through binoculars yielded 54 Monarchs at 7:15, 34 at 7:40 and 13 at 7:55 p.m. By that time the wind was diminishing, the sky clearing and it was beginning to get dark. No large clusters formed as Monarchs simply landed singly.

Similarly, the dune-top group experienced a wafting in of Monarchs that had been too intent on migration to allow time for clustering. With the clouds dissipating we also admired a beautiful sunset over the lake. We had heard that the legs of the beach team did not stop quivering for a while after descending the stairs, so we decided to take the more gently inclined woodland path. Not knowing how far it was, we went as fast as possible, hoping not to stumble over roots or stumps in the quickly enveloping darkness.

It is mind-boggling how many thousands of Monarchs may have floated by that day. And to observe a simultaneous dragonfly migration was simply amazing.

The obligate summer-outing ice cream stop on the way home capped off a perfect evening. Life is good!

Data collected was submitted to Citizen Science Project Journey North: