by Ilse Gebhard, KAWO member

Peninsula Point is at the tip of the Stonington Peninsula jutting out into northern Lake Michigan in the central UP. It is part of the Hiawatha National Forest, which at this location protects a couple of miles of shoreline from development.

The approach to the point is via a one-lane unpaved road through a tunnel of white cedars on either side. Exiting the tunnel, a lighthouse tower, the only remaining structure of a former lighthouse, stands in an open, closely mowed grassy area with cedars along the inland side.

Climbing the circular staircase of the tower gives you a spectacular view with the Garden Peninsula to the east across Big Bay de Noc, the Minneapolis Shoal Light to the south, and Escanaba to the west across Little Bay de Noc. On a clear day you can see the islands at the tip of Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula.

We visited Peninsula Point a number of times over the years and on our visit in 2008, just beyond the tower, there was a 5-foot drop-off and beyond that a spit of land divided into two vegetated lobes. Only five years previous to this visit the water came right up to the drop-off, when the water level of the lake was much higher.

A walk around the vegetated areas was very enlightening. Along with some invasive aliens like Spotted Knapweed and Purple Loosestrife, some very interesting native plants were taking a foothold on this recently exposed limestone shelf. Among these plants were Purple Gerardia, Kalm’s Lobelia, Swamp Thistle, Sneezeweed, Pearly Everlasting, Boneset, Joe-Pye Weed and a number of aster, goldenrod and sedge species. It amazed me how little soil plants need and how quickly they can vegetate an area.

Butterflies were abundant, nectaring mostly, and conveniently for viewing, on the flat tops of the dominant Grass-leaved Goldenrod. In a short time, we had counted nine American Painted Ladies (caterpillar food plant Pearly Everlasting) and more than thirty Common Buckeyes (caterpillar food plant Purple Gerardia). There were numerous Clouded and Orange Sulphurs and Cabbage Whites. Other species identified were Red Admiral, Painted Lady, and Black Swallowtail.

And there were great numbers of Monarchs. Walking along the edge around one of the vegetated lobes we counted more than 300 of them. Monarchs need to store up fat to survive the winter in Mexico. They nectar on flowers on days that the wind direction and speed is unfavorable for migration. Spots like this with abundant flowers and protected from development are of utmost importance to the survival of the monarchs.

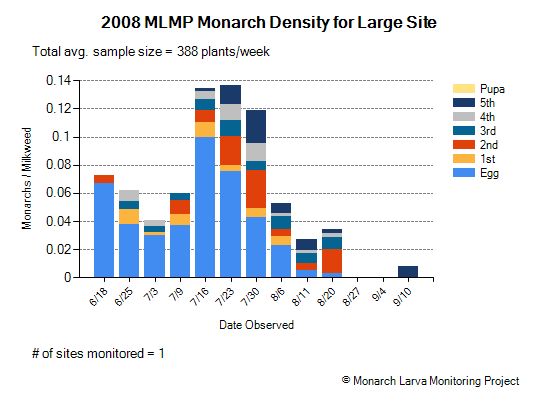

Fall Monarch migration has been studied at Peninsula Point as a stopover site since 1993 and two Monarch Larva Monitoring Project sites (https://mlmp.org) have been established since 1997 just inland from the point at two forest openings with lots of milkweed. See below for monitoring data for 2008 at the larger of the two monitoring sites. Monarchs from Lake Superior south and west of the Straits of Mackinaw reach the Lake Michigan shoreline on their southwest course to the overwintering grounds in Mexico. They prefer not to fly long distances over open water, so they hug the shoreline and eventually end up at Peninsula Point. From there, it is a short hop across Little Bay de Noc to continue their southwest journey through Wisconsin on a favorable northerly wind.

The morning after we had seen all the monarchs out on the spit, we went to the point at sunrise to determine where the monarchs might have roosted overnight – out on the open spit or in the protection of the cedars. The wind had been out of the south when we saw them the day before. The spit with its abundant flower resources was an ideal spot to outwait unfavorable migration conditions and to fatten up. Checking the cedars first, we only spotted a handful of monarchs. Not finding them in the cedars we assumed they must be roosting right where we had seen them nectaring. It was too cool yet for butterflies to fly, and having seen some shorebirds along the edge of the spit the previous day, we next started to scan the shoreline for shorebirds when a bear emerged from behind a coppice of trees about 100 feet from us. The bear appeared to be as surprised as we were and just stood and looked at us. My husband picked up the scope and held it high above his head, to make us appear taller, as we retreated towards the car. Not a time to insist that we were there first.

The bear then proceeded on what appeared to be “its route” around the point, returned to the spot where we had first spotted it and disappeared behind the same trees. While on its route, we watched it through binoculars. It put up numerous monarchs, confirming that indeed they had not migrated and had roosted on the low vegetation on the point and not in the cedars.

All wildlife photos by Russ Schipper.